After Harris Rosen was fired, he needed to figure out what to do next.

His bosses at Walt Disney World didn't believe he would ever become a "company man", and he didn't disagree with them. After his successes in developing the Contemporary, Polynesian and Fort Wilderness resorts, he realized he couldn't be what Disney wanted him to be.

"I finally came to the conclusion that I most likely didn't have the organization man's personality," says Rosen. "I've known since an early age that I've been inflicted with what I call that awful defective entrepreneurial gene. Deep down inside I knew that one day I was destined to be in business for myself."

He wasn't the type of man to play it safe.

So after leaving Disney, he withdrew his last $20,000 from savings and used it as a down-payment on a 256-room Quality Inn on Orlando's International Drive.

Starting Over

As Watergate neared its culmination and the Vietnam War was winding down in 1974, the country was in the middle of an oil embargo. In Orlando, nearly every hotel that wasn't associated with Disney faced a severe financial crisis.

"It was the best possible time to buy a hotel and the worst possible time to buy a hotel," says Rosen.

At the time the hotel had a 20% occupancy rate and the entrepreneur couldn't afford a bus ticket or airfare to reach his customers in New York, New Jersey and Massachusetts.

So he hitchhiked.

His efforts were rewarded. He offered bus companies a rate of $7.25 and $8.25 per night honored for 1 year to come to the hotel. The buses started rolling in and the hotel stayed busy.

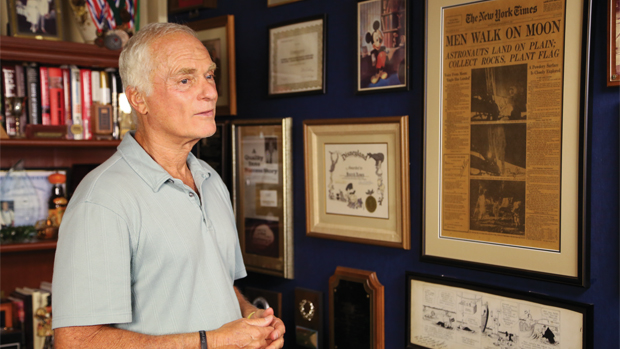

Today, the same Quality Inn hotel continues to defy expectations. His office isn't representative of a successful business man that built the largest independently owned hotel group in Florida. It's more like a cozy living room filled with family photos and mementos from his life, including his U.S. Army ID card and an autographed sketch of a baseball great Jackie Robinson.

"I've been in this room for 37 years," Rosen says. "This is not exactly what people who aspire to be successful dream of having ... beautiful offices and private planes and condos all over the place. But for me, it's very comfortable."

Growing Up

Harris Rosen's first job in hospitality was helping his dad to finish and deliver hand-lettered place cards for banquets. He was paid a penny per card, which was a fortune for the 10-year-old at the time.

"One day, we walk into the elevator and the most magnificent lady, a blonde lady with a beautiful figure, was there with a very tall, distinguished gentleman," he recalls. "I whispered to my dad, "˜Who is that?' ... He turned and said, "˜Ambassador Kennedy, Marilyn, this is my son, Harris.' It was Marilyn Monroe. That sealed it for me. I thought if I could meet all of these incredible people in an elevator, this really was a business that I might enjoy."

Manhattan's Lower East Side in the 40's and 50's was a crowded ghetto riddled with homelessness and afflicted by disease. Rosen and his brother, sons of Ukrainian immigrants, would regularly step over people on the street on their way to school. It wasn't until they heard a passenger remark on a sightseeing bus,"So this is how they live." that they saw there was another way to live.

"My brother and I didn't know what she meant," he says. "Mom had to explain to us that not everyone lives this way. And if we didn't want to live here for the rest of our lives, we had to work hard in school and get a good education."

He took his mom's advice, and earned a bachelor degree in hotel administration from Cornell University.

See how getting an education changed his life and the lives of an entire neighborhood on the next page.

Changing Lives Through Education

"I was having lunch with UCF Professor Abe Pizam, and I told him, "˜One day Abe, I will build you a new school.' At the time, the hospitality program was part of the business school. There were about 75 students," says Rosen.

5 years later, Rosen made good on that promise, pledging $10 million in cash and 20 acres of property.

But his donation didn't come without certain conditions.

"I told President Hitt that I would really prefer the new college be out here near the theme parks, convention center and International Drive ... closer to where all of the action is."

Rosen invited the deans from all the top hospitality colleges in the nation to give their input on the design of the new building. Armed with their suggestions, Rosen's team of architects developed the building. In 2004, the Rosen College of Hospitality Management opened on time and on budget.

"I didn't want to make a fuss out of the UCF donation," Rosen says. "I was ready to just send a check in the mail. But President Hitt implored me not to do it that way. He said, "˜Let us make an announcement. Let us use your name. If people hear that you're doing something, it might encourage others to do something.' When he put it that way, I had to say okay."

Today, there are 3,500 students enrolled at the college and it's the largest hospitality program in the country.

After having his life radically changed thanks to education, Rosen knew this was an area he wanted to focus his efforts on.

Tangelo Park

Tangelo Park is built on land that was once used for orange groves. Originally the housing was for workers, but now it's an isolated residential neighborhood. With few services and little option for public transit the community is well below the poverty line.

A neighborhood that seemed a world away from the theme parks and the pleasures that people flock to Florida for, this area was weighed down by drugs and crime. Nearly half of its students had dropped out of school.

"I fell in love with the neighborhood," says Rosen. "I knew I wanted to do some type of scholarship program for them."

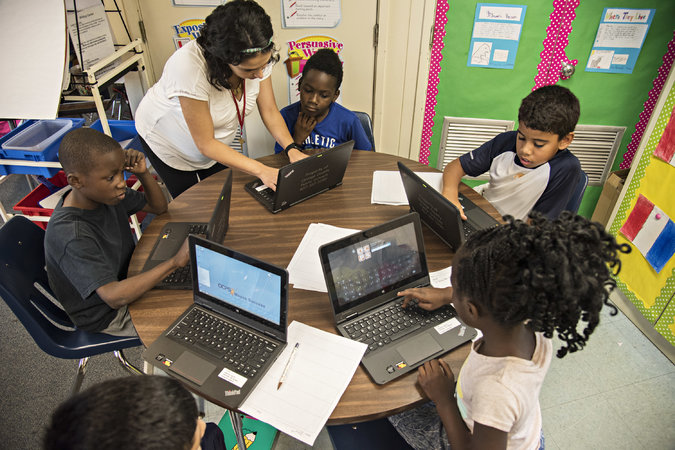

In 1993 he started the Tangelo Park Program which gives every neighborhood child aged 2-4 access to free preschool. Parents also have access to parenting classes, vocational courses and technical training.

For a program that only took 4 people 1 hour to create, the impact on the community has been huge.

Tangelo Park Elementary is now a grade-A school. Every high school senior graduates.

But it doesn't end there.

During his first visit to the elementary school in 1993, he asked the children how many wanted to go to college. "two or three hands went up, and I said, 'that has to change.'" A year later, "every hand went up."

Every high school graduate who is accepted to a Florida public university, community or state college, or vocational school will receive a full Harris Rosen Foundation scholarship which covers their tuition, living and education expenses until they graduate.

Close to 200 students have earned these scholarships, with 75 % of those graduating.

"I was part of the first generation of pre-K children in the Tangelo Park Program. Now I'm about to be the first generation of my family to go to college," says Antionette Butler, a senior at Dr. Phillips High School.

His plan is to attend UCF to study neurology.

Donna Wilcox earned a bachelor's degree in interpersonal/organizational communication at UCF, and then went on to complete a M.A. in mass communications at the University of Georgia.

"When people have the resources to go and succeed, there's a ripple effect," she says. "It becomes generational. No one in my family ever went to college before, but now, my baby sister can't even picture a life without college. My mother even went back and got her degree. I showed her that she could do it."

So far the 75-year-old man has spent $9 million to adopt this neighborhood and it's 2,500 residents. Now he spends about $500,000 a year, less than when he began the program.

"I will be involved in the program until Tangelo Park is a gated community and the average home is selling for $1 million. Then I'm gone."

Source: University of Central Florida / New York Times / Connect Corporate